Introduction

Men at some time are masters of their fates. The fault, clear Brutus, is not in our stars. But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

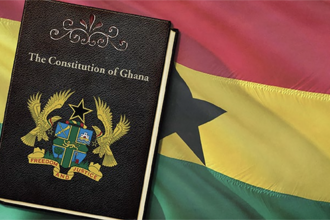

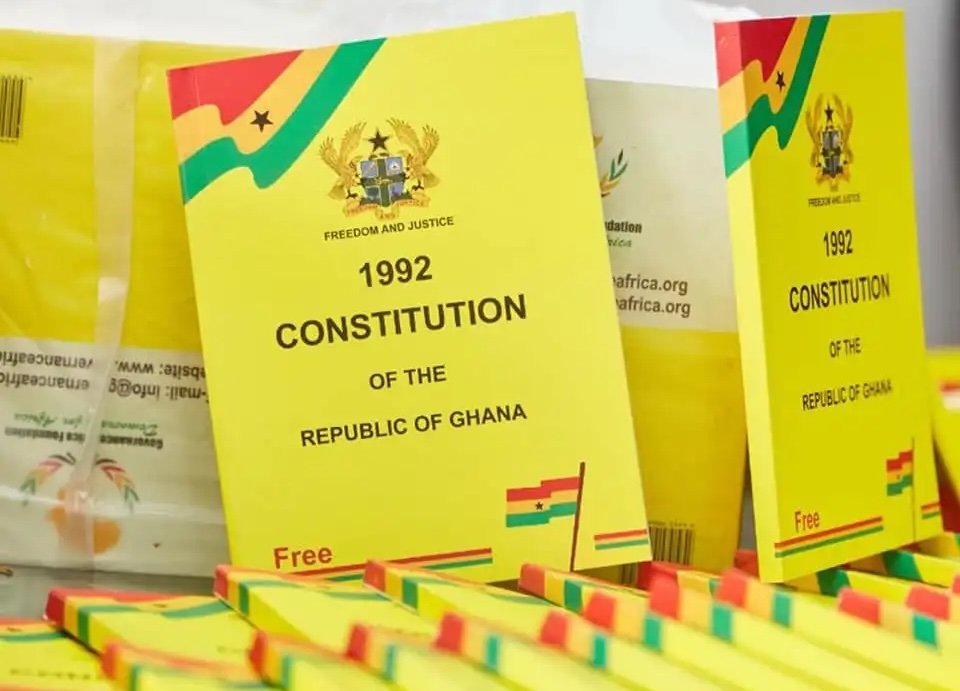

The Constitution outlines the framework for governance including the relationship between the Executive and the Legislative branches of Government. A critical aspect of that relationship is the appointment of Ministers of State. Article 78 (1) of the 1992 Constitution outlines the power of the President of Ghana to appoint Ministers of State. The constitution provides the foundation for parliamentary representation in ministerial appointments by requiring that a significant portion of Ministers be selected from Parliament. This essay makes a case for maintaining the constitutional requirement of having parliamentary representation in Ghana’s ministerial appointments. Amongst other justifications, having a majority of Ministers of State from Parliament can be a cost-effective approach for the state. Since these individuals are already members of Parliament and receiving salaries and benefits, appointing them as Ministers would not incur additional costs for salaries and conditions of service. Indeed, if more, less divides the national purse. By leveraging existing parliamentary structures and personnel, the government can optimize resources allocation and streamline governance. This arrangement fosters a more cohesive and coordinated approach to governance, with Ministers working closely with Parliament to implement policies and programs. While there may be potential drawbacks to this approach, adopting this approach enables government to allocate resources and improve governance.

Majority of Ministers who are members of Parliament

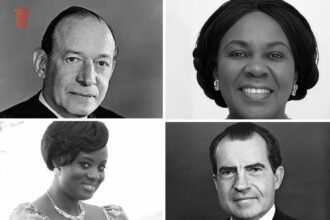

Article 78 (1) of the 1992 Constitution provides that “Ministers of State shall be appointed by the President with the prior approval of Parliament from among members of Parliament or persons qualified to be elected as members of Parliament, except that the majority of Ministers of State shall be appointed from among members of Parliament.” This provision mandates the President to appoint, with prior approval of Parliament. The cry for a change to the provision lies in the fact that we do not know what we want! In 1969, Ghana opted for the British system of parliamentary democracy. Ghanaians cried for change to a different system. Thus, in 1979, Ghana opted for the American system of democracy, forgetting that the United States of America is a federal state. Ghanaians again cried for change and this was done. Under the 1992 Constitution, Ghana opted for what is described as a “hybrid system”. Still, Ghanaians continue to cry for change. In the United Kingdom, ALL of the Ministers of State are appointed from Parliament. In the United States, however, the Vice President presides at the sittings in the Senate, and provides the link between the Executive and the Legislature. In both countries, the system has worked very well for centuries. The system is still working!

The idea behind the hybrid system is that in the Ghanaian set up, there are quite a number of experienced persons who would not want to subject themselves to the abuses and insults at the hustling of parochial party politics. They are willing to serve their country with their expertise. Such persons are eligible to be brought into Cabinet – whatever the colour of their political persuasions – for the good governance of the country. This accords with the National Anthem (2nd verse) which reads, “With our gift of mind and strength of arm. Whether night or day, in mist or storm. In every need whatever the call may be. To serve thee, Ghana…” On the other hand, because of the concept of the elective principle, which still remains a key feature of our political and constitutional architecture, the requirement of parliamentary representation in ministerial appointments is necessary.

A human problem, not a constitutional one

The fault is not in the constitution but rather in the men and women who operate the constitution as well as the men and women we appoint to these high offices of State. An appointment to serve as a Minister of State is a call to action. Many complain that Members of Parliament do not have enough time for their responsibilities as Ministers and as Members of Parliament and as a result, call for an amendment to and total overhaul of Article 78 of the constitution. Respectfully, it is submitted that the problem may not be a constitutional problem or a lack of time problem, but rather lack of a will to serve and be committed to the high-calling of national service (of course, with the exception of some key ministerial positions like that of the Attorney-General & Minister for Justice where the occupier of such office is also a Member of Parliament – it being a very tedious portfolio to combine).

Parliament sits for about twenty-six to twenty-nine weeks of the fifty-two or so weeks of the year. The question then is that what happens to the periods when Parliament is in recess? Day in-day out, Members of Parliament continually seek and are appointed to other work which is not parliamentary work. So why not to the high office of Minister of State. This means that Members of Parliament only need to dedicate themselves to whatever office of service they are appointed to and this requires seriousness and prioritizing of their time and resources. It is important to remind them that “men at some time are masters of their fates” and thus the fault can be found in themselves and not in the stars.

The case for parliamentary representation in Ghana’s ministerial appointments

Aside the cost-saving argument highlighted in the introduction to this essay, parliamentary representation in Ghana’s ministerial appointments allows for Legislative-Executive linkage. Parliamentary representation bridges the gap between the executive and the legislative branches of government and by so doing promotes cooperation and effective governance. By having majority of Ministers coming from Parliament, the Government can ensure that its policies and programs are effectively communicated and implemented through the legislative process. This representation enables Ministers to provide insights into policy formulation and implementation. It also allows Parliament to exercise oversight and hold Ministers accountable for their actions. This arrangement enables the government to respond more effectively to the needs of citizens, ultimately promoting national development and progress.

Furthermore, requiring a majority of ministers to come from Parliament ensures accountability to the people through their elected representatives since members of Parliament are subject to parliamentary oversight, scrutiny and debate and by so doing promoting transparency and good governance. This arrangement allows Parliament to hold Ministers accountable for their actions and policies, to conduct investigations and hearings to ensure transparency and above all provides a platform for citizen’s concerns and grievances to be addressed. By being accountable to Parliament, Ministers are ultimately accountable to the people ensuring that their decisions align with the public interest. This helps to prevent abuse of power, promotes democratic governance and ensures citizen engagement.

Finally, the current constitutional arrangement ensures a representative government in that ministers directly represent the interests of their constituents. As elected representatives, Members of Parliament who are also Ministers of State are able to be familiar with the needs and concerns of their communities and this enables them to articulate and advocate for local interests so as to ensure that government policies address pressing community needs. Constituents are able to provide feedback and this process helps to ensure that government policies are informed and people-centred. Overall, this arrangement enables government to better understand and address the needs of its citizens ultimately leading to more effective and responsive governance.

Conclusion

The constitutional requirement for parliamentary representation in ministerial appointments may have its challenges including the fact that it may serve as a restriction on the pool of talent such that capable persons are excluded from serving as Ministers of State. Also, the requirement serves as a limitation on presidential choice in that it limits the President’s ability to choose qualified individuals, potentially compromising effective governance. Finally, and most challenging is that it Parliamentarians-turned-Ministers may face conflict of interest and as a result may prioritize party or personal interests over national interests. However, the constitutional basis for parliamentary representation in Ghana’s ministerial appointments reflects the country’s commitment to accountability, representation and effective governance. While arguments for and against the requirement highlight the complexity of this issue, it is essential to strike the balance between representation and competence. By examining the constitutional provisions and implications, Ghana can refine its governance framework to promote stability, accountability and development. But at all cost, the current constitutional requirement for parliamentary representation in ministerial appointments should not be abolished totally.

God bless!